German

Deutsche Sprache

Deutsche Sprache

95-100 million (official language countries), 120 million (all countries)

Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy (South Tyrol), Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Belgium, EU, Nordic Council

France (1.2 million), Brazil (0.9 million), Russia (850,000), South Africa (300,000 - 500,000), Kazakhstan (360,000), Poland, Hungary, Romania, Italy, Czech Republic, Namibia, Denmark, Slovakia, Vatican City (Swiss Guard), Venezuela (Colonia Tovar)

US, Argentina, Canada , Mexico, Australia, Chile, Paraguay, New Zealand, Bolivia, Netherlands, UK, Peru, Spain, Poland, Israel, Norway, Ecuador, Ukraine, Dominican Republic, Greece, Ireland, Belize

German is an official language in seven EU countries, and the largest language of the union. However, it is not an international language like English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. First, German emigration to other continents, though substantial, was individual and state-less, without the military or cultural support of an empire. Thus, over time, tens of millions of German settlers in the Americas, Southern Africa and Oceania have been absorbed by their host nations and lost their language. Second, two world wars have reduced the German-speaking territories and led to loss of goodwill (to put it mildly) and the closure of cultural institutions such as schools in countries like the US and Brazil. A notable exception of the general numerical decline of German is the Amish community in the US, with a yearly(!) growth rate of almost 5%, which in theory should make them the largest US population group by the turn of the century.

High German consonant shifts

(bdg→ptk, th→d, v→b, k→ch, p→pf, t→ts/ss)

Hohenstaufen: Alemannic-based literary standard

Eastward expansion

Teutonic-Order state in the Baltics Early Yiddish

(Middle High German with Hebrew letters)

Hanseatic League Low German administration

Printing press (Gutenberg)

Mass emigration to America

Standard High German (Hochdeutsch) becomes a spoken language

Standardization

(2nd Orthographical Conference)

Spelling reform

| Century | Shifted (High German) | Unshifted (English) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| d→t | 2-4 | gut | good |

| p→ff | 4/5 | Schiff | ship |

| t→ss | 4/5 | essen | eat |

| k→ch | 4/5 | machen | make |

| t→ts | 5/6 | Zehe | toe |

| p→pf | 6/7 | Apfel | apple |

| ß→b | 7/8 | geben | give |

| b→p | 8/9 | Rippe | rib |

| d→t | 8/9 | Tag | day |

| dg→ck | 8/9 | Brücke | bridge |

| þ→d | 9/10 | Dorn | thorn |

German has a 26-letter alphabet, but uses umlaut diacritics on a, o and u (ä, ö, ü), as well as a special letter (ß) for voiceless s after long vowels.

German has an etymological spelling style out of touch with current pronunciation, however, pronunciation can (usually) be predicted from the written form. Examples of special spelling conventions are sch /ʃ/ (Schale 'bowl'), st /ʃt/ (Stoff 'fabric'), sp /ʃp/ (Spaß 'fun') and the diphthongs ei /a͡ɪ/ (Ei 'egg') and eu /ɔʏ̯/ (Heu 'hay').

There is a famous children's song that nicely demonstrates the German sound system: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9ylfF-sYf4

Three Chinese with a double bass sat on the street and talked. Along came the police: Now what is this? - Three Chinese with a double bass.

The song is repeated many times, each time replacing all vowels with one and the same vowel or diphtong, for instance 'a': Dra Chanasan mat dam Kantrabass ..., 'ö': Drö Chönösön möt döm Köntröböss ..., or even 'au': Drau Chaunausen maut daum Kauntraubauss ....

German has four cases and three grammatical genders, with agreement between articles, adjectives and nouns. The declination of adjectives differs depending on whether the noun phrase is definite or indefinite. Interestingly, German nouns themselves have almost no case inflection, the inflection marker resides mainly in the article. A special trait of German is the use of umlaut for inflections. Thus many German nouns mark plural by changing the stressed vowel: a/o/u → ä/ö/ü.

|

Male the grey wolf/wolves |

Female the little mouse/mice |

Neuter the fast horse/horses |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | der graue Wolf die grauen Wölfe |

die kleine Maus die kleinen Mäuse |

das schnelle Pferd die schnellen Pferde |

| Genitive | des grauen Wolf(e)s der grauen Wölfe |

der kleinen Maus der kleinen Mäuse |

des schnellen Pferd(e)s der schnellen Pferde |

| Dative | dem grauen Wolf den grauen Wölfen |

der kleinen Maus den kleinen Mäusen |

dem schnellen Pferd den schnellen Pferden |

| Accusative | den grauen Wolf die grauen Wölfe |

die kleine Maus die kleinen Mäuse |

das schnelle Pferd die schnellen Pferde |

| Male a grey wolf/wolves |

Female a little mouse/mice |

Neuter a fast horse/horses |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ein grauer Wolf grauen Wölfe |

eine kleine Maus kleine Mäuse |

ein scnnelles Pferd schnelle Pferde |

| Genitive | eines grauen Wolf(e)s grauer Wölfe |

einer kleinen Maus kleiner Mäuse |

eines schnellen Pferd(e)s schneller Pferde |

| Dative | einem grauen Wolf grauen Wölfen |

einer kleinen Maus kleinen Mäusen |

einem schnellen Pferd schnellen Pferden |

| Accusative | einen grauen Wolf graue Wölfe |

eine kleine Maus kleine Mäuse |

ein schnelles Pferd schnelle Pferde |

Verbs inflect for person and number, and agree with the subject. Apart from inflectional endings, a large number of German so-called strong verbs have internal vowel changes to mark tense inflection, and umlaut occurs in 2nd and 3rd person singular verb forms, as well as in the past subjunctive.

| schlafen

(to sleep) |

Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person |

Ich schlafe (I sleep) Ich schlief (I slept) |

Wir schlafen (we sleep) Wir schliefen (we slept) |

| 2nd person |

Du schläfst (you sleep) Du schliefst (you slept) |

Ihr schlaft (you sleep) Ihr schlieft (you slept) |

| 3rd person |

Er/sie/es schläft (he/she/it sleeps) Er/sie/es schlief (he/she/it slept) |

Sie schlafen (they sleep) Sie schliefen (they slept) |

German is famous for having a large lexicon. This is due in part to a long literary tradition accumulating synonyms from many ages and dialects, as well as the fact that German allows word compounding (Apfelsaft), where English uses chains of noun (apple juice) and French prepositional phrases after nouns (jus de pomme). Interestingly, the German Wikipedia is the 2nd largest in the world, and much bigger than one would expect given the number of German speakers.

Yet another reason for the size of the German lexicon is the mighty German bureaucracy, needing a bureaucratic word for everything from Postwertzeichen (Briefmarke - stamp) to Personenkraftwagen/PKW (Auto - car).

Thus, when applying for a driver's license, a simple "no" may sound like this: Ihr Antrag auf Einleitung eines Verfahrens zur Erteilung der Erlaubnis zum Führen eines Kraftfahrzeugs auf öffentlichen Straßen wurde abgelehnt. (Your application for the initiation of proceedings aiming at the conferral of a permission to drive a motor vehicle on public streets was refused).

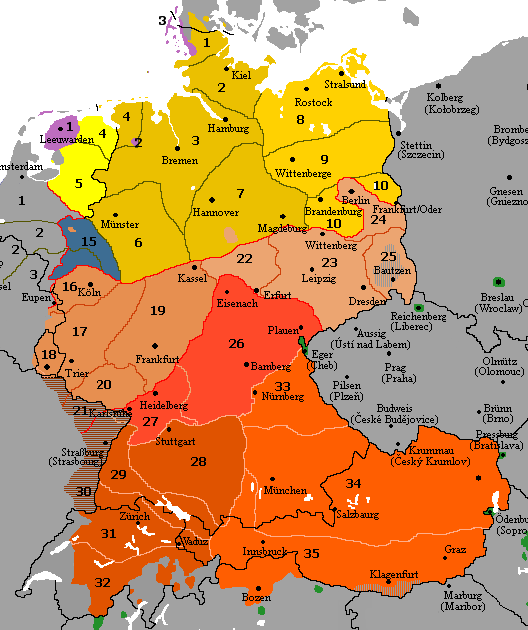

The German dialectal landscape is very complex, in part because the language area for most of its history was a political patchwork of sovereign areas only loosely held together by an elected emperor. In dialectal terms, the most famous border is a north/south soundshift divide running roughly through Frankfurt, with b/d/g north and p/t/k south. Dialectal differences don't stop at sound shifts though, but are also found in the lexicon. Rolls, for instance, are Brötchen in the North, and Wecken or Semmel in the South, mutating through Weckerl and Semmerl in Bavaria to Weggli and Semmeli in Switzerland. Further northern variants include Schrippe (Berlin), Luffe (Braunschweig) and the Danish-equivalent Rundstück (da: rundstykke).

Low

Central

Upper

Multilingual website for learning German: http://deutsch.info