Irish

Gaeilge

Gaeilge

No official figure, about 100.000; 2 million claim knowledge based on school study.

Ireland, EU

Northern Ireland

USA, Canada, Australia, UK, Argentina, New Zealand

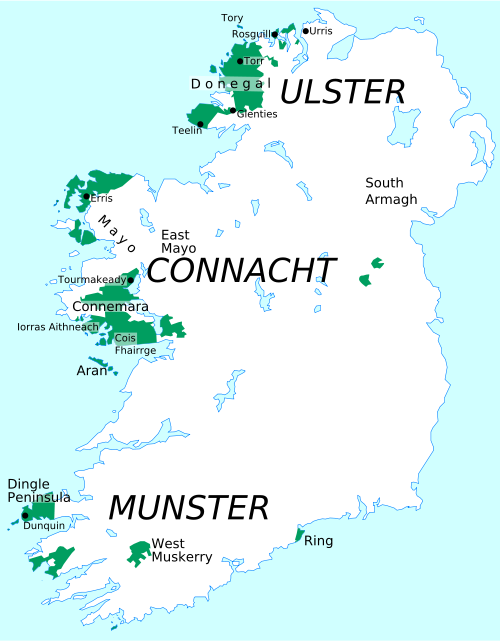

Irish is unusual in that, like English, fluent learners outnumber native speakers, and studies have shown that about one third of those who speak it daily are not native speakers. On the other hand, some native Irish speakers living in English-speaking parts of Ireland (known as the Galltacht, the “area of foreign speech”) may rarely have the opportunity of speaking Irish. There is a rather extreme form of politeness in vogue – the entry of one English-speaking monoglot can make a room full of Irish speakers switch to English. The areas where Irish remains the community language are known as the Gaeltacht.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Irish is one of the oldest literary languages in Europe, with a text, Amra Choluim Chille, the Lament for Saint Colm Cille or Columba, dating from 597 AD. It had been a literary language 1,410 years when it became an official EU language on 1 January 2007. The use of Irish was banned by the English occupation through the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366. A subsequent version of the Statutes ordained that “Every Englishman must learn English, or be treated like an Irish enemy”! Yet when Henry VIII of England proclaimed himself “King of Ireland” in 1541, the proclamation had to be translated into Irish so that the parliament of the English colony in Dublin could understand it!

Despite centuries of attempts to destroy it, Irish remained the majority language of Ireland until the Great Famine in 1845-49, when 1-2 million people died of hunger. It had almost died out by the end of the 19th century, yet when Ireland became independent in 1922, the first decision of the first Irish Government was that all children in all primary and secondary schools should study Irish for at least one hour per day. The Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which ended political violence in Northern Ireland, contains 3 pages of British Government commitments to promote Irish.

The grammar is very complex. There is extensive initial mutation, that is the beginnings of words change, for example a cosa (her legs); a chosa (his legs); a gcosa (their legs). There is no verb “to have”, but the verb “to be” reflects both the ser/estar distinction of Spanish (is/tá in Irish, e.g. is bean í (she is a woman); but tá sí anseo, (she is here)); and the jest/bywa distinction of Polish (tá/bíonn in Irish, e.g. tá sí anseo (she is here now), but bíonn sí anseo (she is habitually here)).

Irish has separate sets of numerals for counting humans and non-humans: "two horses" is dhá chapall, but "two people" is simply beirt.

In common with Hungarian, Irish describes one of a pair as “half”, e.g. ar leathchois (one-legged), literally “with half a leg”; ar leathshúil (one-eyed), etc.

Gabh mo leithscéal = excuse me, literally, "accept my half-story".